Type of Home Healthcare Devices

Home health care devices span a wide range, as mentioned above. Table 8-1 presents a taxonomy that uses the following major categories:

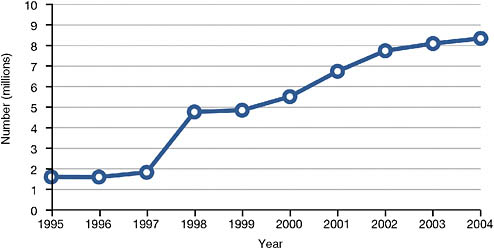

FIGURE 8-1 Medicaid home care recipients, 1995-2004.

SOURCE: Data from National Association for Home Care and Hospice (2008).

-

Medication Administration Equipment—devices used to administer medications in tablet, liquid, or aerosol form.

-

Test Kits—kits used for measuring the presence of various chemicals in blood or urine.

-

First Aid Equipment—equipment used to care for injuries or temporary conditions.

-

Assistive Technology—devices used to enhance personal capabilities, such as sensory abilities or mobility.

-

Durable Medical Equipment—includes medical devices used to support performance of basic activities of daily living, such as beds, lifts, and toileting equipment.

-

Meters/Monitors—includes a wide range of devices for determining health status or managing disease conditions, either one time or on an ongoing, intermittent basis.

-

Treatment Equipment—equipment used to administer various medical therapies.

-

Respiratory Equipment—equipment used to treat respiratory conditions.

-

Feeding Equipment—devices used for feeding.

-

Voiding Equipment—devices used for releasing urine or feces from the body.

-

Infant Care—includes machines used to monitor and treat infants.

-

Telehealth Equipment—equipment used to collect data in the home environment and transmit the data to a remote monitoring site.

TABLE 8-1 Types of Home Health Care Devices

|

Category |

Device |

|

Medication Administration Equipment |

Dosing equipment (e.g., cups, eyedroppers, blunt syringes) Nasal sprays, inhalers Medication patches Syringes/sharps |

|

Test Kits |

Pregnancy test Male/female/stress hormone test Cholesterol test Allergy test Bladder infection test HIV test Hepatitis C test Drug, alcohol, nicotine test |

|

First Aid Equipment |

Bandages Ace bandage, compression stocking Snakebite kit Heating pad Traction Ostomy care Tracheotomy care Defibrillator |

|

Assistive Technology |

Eyeglasses Hearing aid Dentures (full or partial) Prosthetic device Orthotic device, including braces Cane or crutches Walker Wheelchair Scooter |

|

Durable Medical Equipment |

Hospital bed Specialized mattress Chair (e.g., geri-chair or lift chair) Lift equipment Commode, urinal, bed pan |

|

Meters/Monitors |

Thermometer Stethoscope Blood glucose meter Blood coagulation (PT/INR) meter Pulse oximeter Weight scale Blood pressure monitor Apnea monitor Electrocardiogram monitor Fetal monitor |

|

Category |

Device |

|

Treatment Equipment |

IV equipment Infusion pumps Dialysis machines Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation systems |

|

Respiratory Equipment |

Ventilator, continuous positive airway pressure, bi-level positive airway pressure, and demand positive airway pressure equipment Oxygen cylinder Oxygen concentrator Nebulizer Masks and canulas Respiratory supplies Cough assist machine Suction machine Manual resuscitation bags |

|

Feeding Equipment |

Feeding tubes (nasogastric, gastrostomy, jejunostomy) Enteral pump |

|

Voiding Equipment |

Catheter Colostomy bags |

|

Infant Care |

Incubator Radiant warmer Bilirubin lights Phototherapy Apnea monitor |

|

Telehealth Equipment |

Cameras Sensors Data collection and communication equipment (e.g., computer) Telephone or internet connections |

EMERGENT TECHNOLOGIES IN HOME HEALTH CARE

Telehealth—which is health care facilitated by telecommunications technology—has begun to transform the home care landscape and promises to grow substantially in coming years. Currently, simple technologies (e.g., e-mail, the Internet, cell phones) can be used to monitor people’s health at a distance. High-resolution visual images and audio can be transmitted through telephone lines or broadband connections. In coming years, remote monitoring will increase dramatically and will involve more types of equip-

ment in the home; technologies such as wireless electronics and digital processing will support communication between a diverse set of devices and remote health care providers. Some wireless devices, especially meters and monitors, will be wearable, which will make constant monitoring possible or intermittent testing more convenient.

Telehealth technologies can be used to support adherence to treatment regimens, facilitate self-care, and provide patient education. Cameras and sensors can be used to track patient movements and behaviors in the home. Monitors can collect and transmit a variety of data to health care providers at a distance, eliminating the need to visit a clinic or to call in. These technologies can also provide reminders to people at home, such as to take medications, measure their blood pressure, perform physical therapy, or schedule follow-up appointments.

Future technological advances will bring new devices, such as improved pacemakers, cochlear implants, and medicine delivery systems. Miniaturization of various components, including microprocessors and nanotechnology, will make possible advances to many types of medical devices used inside and outside formal health care settings. Some of the devices envisioned will be embedded in common household objects, such as a biosensing chip in a toothbrush that will check blood sugar and bacteria levels; smart bandages made of fiber that will detect bacteria or a virus in a wound and then recommend appropriate treatment; smart T-shirts that will monitor the wearer’s vital signs in real time; and heads-up displays for glasses that use pattern recognition software to help people remember human faces, inanimate objects, or other data. Novel handheld devices may provide new capabilities for home health care, such as skin surface mapping, an imaging technology that will track changes in moles to detect malignancies; biosensors that will perform as portable laboratories; and alternative input devices such as eye blinks (electromyography) or brain activity (electroencephalography) that will facilitate hands-free device control, which will be especially useful for people with limited use of their hands (e.g., people with paralysis or arthritis) (Lewis, 2001).

Some people envision a future with more consumer-driven, preventive medicine in which consumers can evaluate their own bodies and communicate with health care professionals on an ongoing or as-needed basis. Other people are less optimistic that the nation will ever get to a preventive medicine model of health care, given the current business model being followed in the United States. The reality will probably fall between the two extremes, with some portion of the U.S. population making good use of new opportunities to follow good health maintenance practices. If medical devices are well-designed with appropriate and effective application of human factors principles and methods that percentage can be maximized. Chapter 9 provides more information on networked health technology for home care.

HUMAN FACTORS ISSUES FOR HOME HEALTH CARE DEVICES

User Issues

The characteristics of individuals who use medical devices in the home are not well known by many medical device designers. Indeed, some designers do not understand well even the needs of “average” users, and home device users often have capabilities that are far different from average. Particularly due to the conditions that require them to need home health care, individuals receiving care at home may have reduced physical strength or stamina (e.g., fatigue associated with chronic pain), diminished visual or hearing abilities, impaired cognitive abilities (including confusion caused by the effects of medication), or combinations of these conditions. Illness, medications, and stress can intensify the severity of any preexisting limitations in the user’s physical, perceptual, and cognitive functions.

People’s ability to operate a medical device depends on their personal characteristics, including the following:

-

physical size, strength, and stamina;

-

physical dexterity, flexibility, and coordination;

-

sensory capabilities (i.e., vision, hearing, tactile sensitivity);

-

cognitive abilities, including memory;

-

comorbidities (i.e., multiple conditions or diseases);

-

literacy and language skills;

-

general health;

-

mental and emotional state;

-

level of education and training relative to the medical condition involved;

-

general knowledge of similar types of devices;

-

knowledge of and experience with the particular device;

-

ability to learn and adapt to a new device; and

-

willingness and motivation to use a new device.

It is important to recognize that lay users may also be affected by their own emotional states, which may be caused or aggravated by the news that they or their loved ones are seriously ill. They may be overwhelmed by new terminology and the critical responsibilities associated with home care, including awareness of the potential for harm—to the equipment, to their loved ones, or to themselves—if they make an error. Instructions may be confusing, and users may have little preparation and insufficient personal or institutional support for the tasks they must perform.

Regardless of their capabilities, individuals using medical devices in the home should be able to use the devices safely and effectively and without

unintentionally making errors that could compromise the health of the person receiving care (Kaye and Crowley, 2000). This requirement has implications for medical device design, user training programs, and ongoing support. If the human factors demands of the medical device exceed the capabilities of the user, the equipment burden may be too great to manage, and the person receiving home health care may be forced to move to a long-term care facility or a nursing home.

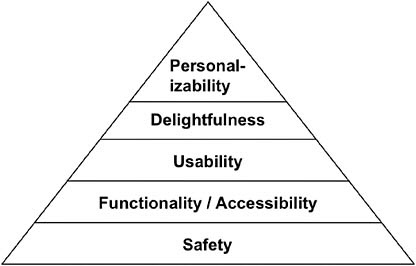

In 2005, Hancock, Pepe, and Murphy proposed a “hierarchy of ergonomics and hedonomic needs” (see Figure 8-2). The purpose of the article was to suggest that once people’s needs for safety and functionality were fulfilled, designers should address the need for pleasure.

This hierarchical structure could also represent the relationships among safety, accessibility, and usability. For individuals with any sort of physical, sensory, cognitive, or emotional disability, accessibility equates to functionality. The primary imperative is that home-use medical devices be safe; the secondary imperative is that they be functional (accessible) for the people who need to use them. Ideally, devices would satisfy all levels of the pyramid: they would be safe and functional, but also usable and pleasurable, and even offer customization to individual users’ needs and preferences. There is no reason why medical devices, especially those intended for personal use, cannot be satisfying to use and aesthetically pleasing, and possibly even enable users to achieve their own health and life goals.

FIGURE 8-2 Hierarchy of ergonomic needs.

SOURCE: Adapted from Hancock, Pepe, and Murphy (2005).

Device Issues

Some medical devices may not be safe for all users or use environments, but medical device manufacturers have a responsibility to recognize and mitigate hazards to the greatest extent possible. In the FDA guidance document, Medical Device Use-Safety: Incorporating Human Factors Engineering into Risk Management, Kaye and Crowley (2000, p. 7) explain that use-related hazards occur for one or more of the following reasons:

-

Devices are used in ways that were not anticipated.

-

Devices are used in ways that were anticipated, but inadequately controlled for.

-

Device use requires physical, perceptual, or cognitive abilities that exceed those of the user.

-

Device use is inconsistent with user’s expectations or intuition about device operation.

-

The use environment … [affects] device operation and this effect is not understood by the user.

-

The user’s physical, perceptual, or cognitive capacities are exceeded when using the device in a particular environment.

The FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health collects data on adverse event incidents associated with medical devices. One of the FDA databases is the Medical Product Safety Network (MedSun), in which more than 350 health care facilities (primarily hospitals) currently participate and submit reports through the Internet. The database has several subnetworks that focus on specific clinical areas, including HomeNet, which focuses on medical devices used in the home environment (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2009b).

Another FDA database collects reports from manufacturers and health care professionals in the Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) database. The data include all voluntary adverse event reports since June 1993, user facility reports since 1991, distributor reports since 1993, and manufacturer reports since August 1996. (User facilities are defined as hospitals, nursing homes, long-term care facilities, and ambulatory and outpatient treatment facilities, including home care and hospice care.)

In evaluating reports of adverse device events in the MAUDE database between June 2008 and August 2009, the FDA found 1,059 events for which the location of the event was reported as “home.” The devices involved in the greatest number of events were

-

insulin infusion pump,

-

implantable cardioverter defibrillator,

-

automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator with cardiac resynchronization,

-

ventricular (assist) bypass device,

-

mechanical walker,

-

implantable pacemaker pulse generator,

-

piston syringe,

-

intravascular administration set, and

-

continuous ventilator (facility use) (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2009d).

Note that this list identifies the types of devices with which professionalshave had greatest difficulty in the home; lay users do not have access to these reporting systems, nor do they have any good mechanism for providing this type of feedback to the FDA.

Infusion pumps, the most frequently reported device on this list, are notoriously complicated to operate and put a particularly high cognitive burden on the user. This is especially problematic because the person receiving infusion tends to be sicker than the typical home health care recipient and the medications are more critical; consequently, the margin for error is small.

Three of the most common use errors when administering intravenous medications via a pump are (1) dosage miscalculation, (2) transcription data entry error, and (3) titration of the wrong medication. For home use, the first two errors (both of which result in wrong dosage) are less likely if a professional sets up the pump when it first enters the home. The third error (wrong medication) is more likely, especially if the person receiving care uses more than one type of medication. In any use scenario, the pump operator may accidently and erroneously change the rate of drug delivery. All of these types of errors can be life-threatening.

The MAUDE database contains a report of a dosing incident involving an individual who had been using an insulin pump for about 4 years. He had been using his previous pump for 2 years but had purchased a new one 3-4 months before the incident. A few hours after he arrived home one evening, he was found unconscious in his bedroom and could not be revived by paramedics. His cause of death was determined to be a severe hypoglycemic insulin reaction. The report said, “User reported having difficulties with pump outputs. No similar pump issues with older style pump” (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2009c). This suggests possible usability problems with the new pump.

To minimize the possibility of pump use errors, it is important that the pump clearly display the type of drug and infusion dose rate. If the pump

has built-in intelligence and self-checks (e.g., bar code recognition, reference drug libraries, dosing limits, and best-practice guidelines), or transmits data to a remote health care facility, the chance of error is reduced (B. Braun Medical, Inc., 2000; Beattie, 2005; DiConsiglio, 2005).

Another example of home device user difficulty involved a home ventilator. A family member went into the patient’s room one night and discovered that the patient had died and his ventilator was not functioning. The family member reported that no alarm had sounded and there was a problem with the ventilator’s power cord. The police officer who arrived at the house manipulated the power cord’s plug at the wall outlet, and the ventilator powered up again (Weick-Brady and Lazerow, 2006, p. 203).

Medical devices used in the home should be easy for lay users to operate and have minimal requirements for calibration and maintenance. While hospitals have departments dedicated to performing these tasks, lay users should not be expected to have this level of interaction with equipment. Devices should be self-calibrating whenever possible. Maintenance should generally be limited to only the most basic, routine functions, such as simple cleaning and battery replacement. Depending on the device involved, however, some home care providers will need to sterilize components or dispose of used supplies, and the device system should be designed so that these tasks are easy to perform.

Human Factors Standards and Guidance

U.S. and international standards provide guidance to industry on the importance of and methods for applying human factors to medical device design. Standards offer companies models for including various processes in corporate operating procedures and allow them to utilize bodies of knowledge about best design practices without having to conduct their own research. Following standards enables companies to demonstrate to the FDA (and other regulatory bodies) that they have applied best practices.

One of the key U.S. standards is referred to as ANSI/AAMI HE74:2001, Human Factors Design Process for Medical Devices. The document describes “a recommended human factors engineering process for use in fulfilling user interface design requirements in the development of medical devices and systems, including hardware, software, and documentation.” The standard includes an overview and a discussion of the benefits of human factors engineering, a review of the human factors engineering process and its analysis and design techniques, and a discussion of implementation issues.

One of the most important international standards is ISO/IEC 62366:2007, Medical Devices—Application of Usability Engineering to Medical Devices, which refers to and builds on HE74. Its abstract says that the document:

Specifies a process for a manufacturer to analyze, specify, design, verify and validate usability, as it relates to safety of a medical device. This usability engineering process assesses and mitigates risks caused by usability problems associated with correct use and use errors, i.e., normal use. It can be used to identify but does not assess or mitigate risks associated with abnormal use. If the usability engineering process detailed in this International Standard has been complied with and the acceptance criteria documented in the usability validation plan have been met, then the residual risks, as defined in ISO 14971, associated with usability of a medical device are presumed to be acceptable, unless there is objective evidence to the contrary.

ISO/IEC 62366 incorporates HE74 as an informative appendix (with the exception of a description of the relationship between HE74 and the FDA Quality Systems Regulation). These two documents describe human factors methods that may be applied to assess device safety and performance.

A new standard, ANSI/AAMI HE75:2009, Human Factors Engineering—Design of Medical Devices, supplements these process documents with design guidelines. The recommended practice is approximately 500 pages long and is organized into 25 sections, including one explicitly on home health care. In an interview in August 2008, shortly before his retirement as the FDA’s human factors team leader, Peter Carstensen praised the document but cautioned against applying its contents without judgment (Swain, 2008, p. 52):

HE75 is a very comprehensive handbook describing almost everything a designer needs to know. It’s a one-stop shopping text with most all the information a designer would need to design a good user interface and validate it. But it still requires intelligent interpretation. It’s like someone could write a detailed text on how to perform brain surgery, but careful study and practice will be needed to pull it off. HE75 is a very good start but it’s not a substitute for expertise in the field.

HE75 is massive and may be difficult to apply for engineers and designers who are unfamiliar with human factors and do not know how to prioritize the recommendations for a particular device or how to choose among the inevitable trade-offs that must be made when guidelines conflict. Human factors engineering is an art as well as a science and must be practiced differently for every application.

To complement national and international standards, guidance associated with the concept of universal design provides useful information related to the needs of lay users. Universal design considers the needs of the broad spectrum of potential design users, which is relevant when designing medical devices (Story, 2007), especially for home use.

In 1995 a group of architects, product designers, engineers, and envi-

ronmental design researchers convened to articulate the fundamental concepts that underlie universal design. The purpose of the resulting document, called The Principles of Universal Design (see Table 8-2), was to support evaluation of existing designs, inform development of new designs, and educate both designers and consumers about the characteristics of more usable products and environments (Connell et al., 1997; Story, Mueller, and Mace, 1998). Implicitly, their purpose was to integrate accessibility into as much of the built environment as possible in order to make it more usable by people of all ages and abilities or disabilities.

Below are examples of how the principles can be applied to medical devices for home health care.

-

Principle 1. Equitable Use—i.e., design for all. Optimizing universal accessibility can increase the number of people for whom a medical device, such as a dialysis machine, is appropriate and therefore extend the option of home health care to more people.

-

Principle 2. Flexibility in Use—i.e., design for each. A bed control can accommodate users’ personal characteristics, abilities, and preferences if it can be operated with a variety of switches that can be activated with a variety of body parts (e.g., hand, foot, cheek).

-

Principle 3. Simple and Intuitive Use—i.e., design for the mind. User interfaces for pumps (e.g., infusion, insulin, enteral) should be easy to understand and intuitive and logical to use.

-

Principle 4. Perceptible Information—i.e., design for the senses. A blood coagulation (PT/INR) meter should transmit information in multiple sensory modes in order to maximize communication. It could allow users to enlarge the size of the information on the display (for people with vision impairments) and offer voice output (for people who are blind or who understand auditory information better than visual). The voice output should have a volume control (for people with different hearing abilities) that can be turned off (for people who cannot or do not want to hear it).

-

Principle 5. Tolerance for Error—i.e., design for error. Having the device’s user interface request confirmation of irreversible or potentially critical operations can reduce the chance of inadvertent actions. Having devices that revert to benign settings when the operator takes no action for a period of time, or that automatically shut off in case of a power surge (such as by using a ground-fault interrupter), can reduce the level of hazard.

-

Principle 6. Low Physical Effort—i.e., design for limited strength and stamina. Buttons that activate in response to body heat require no force (however, they are unusable for people with limb pros-

TABLE 8-2 The Principles of Universal Design

|

Principle |

Definition and Guidelines Associated with Principle |

|

1. Equitable Use |

The design is useful and marketable to people with diverse abilities. |

|

1a. |

Provide the same means of use for all users: identical whenever possible; equivalent when not. |

|

1b. |

Avoid segregating or stigmatizing any users. |

|

1c. |

Make provisions for privacy, security, and safety equally available to all users. |

|

1d. |

Make the design appealing to all users. |

|

2. Flexibility in Use |

The design accommodates a wide range of individual preferences and abilities. |

|

2a. |

Provide choice in methods of use. |

|

2b. |

Accommodate right- or left-handed access and use. |

|

2c. |

Facilitate the user’s accuracy and precision. |

|

2d. |

Provide adaptability to the user’s pace. |

|

3. Simple and Intuitive Use |

Use of the design is easy to understand, regardless of the user’s experience, knowledge, language skills, or current concentration level. |

|

3a. |

Eliminate unnecessary complexity. |

|

3b. |

Be consistent with user expectations and intuition. |

|

3c. |

Accommodate a wide range of literacy and language skills. |

|

3d. |

Arrange information consistent with its importance. |

|

3e. |

Provide effective prompting and feedback during and after task completion. |

|

4. Perceptible Information |

The design communicates necessary information effectively to the user, regardless of ambient conditions or the user’s sensory abilities. |

|

4a. |

Use different modes (pictorial, verbal, tactile) for redundant presentation of essential information. |

|

4b. |

Maximize “legibility” of essential information (in all sensory modes). |

|

4c. |

Differentiate elements in ways that can be described (i.e., make it easy to give instructions or directions). |

|

4d. |

Provide compatibility with a variety of techniques or devices used by people with sensory limitations. |

|

5. Tolerance for Error |

The design minimizes hazards and the adverse consequences of accidental or unintended actions. |

|

5a. |

Arrange elements to minimize hazards and errors: most used elements, most accessible; hazardous elements eliminated, isolated, or shielded. |

|

5b. |

Provide warnings of hazards and errors. |

|

5c. |

Provide fail-safe features. |

|

5d. |

Discourage unconscious action in tasks that require vigilance. |

|

6. Low Physical Effort |

The design can be used efficiently and comfortably and with a minimum of fatigue. |

|

6a. |

Allow user to maintain a neutral body position. |

|

6b. |

Use reasonable operating forces. |

|

6c. |

Minimize repetitive actions. |

|

6d. |

Minimize sustained physical effort. |

|

Principle |

Definition and Guidelines Associated with Principle |

|

7. Size and Space for Approach and Use |

Appropriate size and space is provided for approach, reach, manipulation, and use regardless of user’s body size, posture, or mobility. |

|

7a. |

Provide a clear line of sight to important elements for any seated or standing user. |

|

7b. |

Make reach to all components comfortable for any seated or standing user. |

|

7c. |

Accommodate variations in hand and grip size. |

|

7d. |

Provide adequate space for the use of assistive devices or personal assistance. |

|

SOURCE: Connell et al. (1997). |

|

-

theses or cold hands). Some devices may be controlled with voice commands.

-

Principle 7. Size and Space for Approach and Use—i.e., design for body sizes and postures. A medical device should provide clearance for people who use it. The diameter of a cylindrical handhold can be tapered to allow users to place their hands along whichever section best suits the size of their hands as well as their needs and preferences for the specific task.

These universal design principles can help improve accessibility and usability (and safety) for laypeople who operate medical devices in the home.

Device Labeling and User Training Issues

Device labeling, instructions, and training can all affect the occurrence of use errors. Use errors may be categorized as either active or latent. Active errors have immediate and potentially serious consequences, such as from an incorrect medication dose or an injection in an incorrect site. Latent errors occur on an ongoing basis and can be much more difficult to identify, such as failure to replace the code key on a blood glucose meter or placing old test strips into a vial of new strips that have a different code (Patricia Patterson, Agilis Consulting Group, personal communication, 2004).

Instructions and labeling that accompany medical devices used in the home must also be designed for lay users. Too often, medical device documentation and labeling are written not for novice users but for health care professionals—that is, to the education and knowledge levels of people who know about medical technology in general and the subject device in

particular. Poor labeling increases the likelihood that users will need to call either the doctor’s office or the device manufacturer’s customer service line, which is expensive and may not answer all the user’s questions. User confusion can lead to use errors or product abandonment, either of which compromises quality of care.

All home caregivers, whether professional or lay, must be adequately trained to use and maintain the medical devices that they will use in the home. All household residents who are capable should learn how to interact with the medical equipment. Some residents should be taught about the limits of their involvement, such as children who may be taught to get help if an alarm sounds.

Home users may have multiple problems with training. As described by Fisk and colleagues (2004, p. 131):

The training may be provided under the stressful and emotional context of being newly diagnosed with an illness. Training provided by a health care professional may be presented too quickly, using jargon, with little practice by the patient, and without adequate explanation of the difficulties that may arise if the steps are not followed properly. When users are at home attempting to use a system, they may forget the details of the steps, have no idea about what to do if the system does not operate as expected, and have no immediate access to help.

Lack of ongoing training and support is a particular challenge when device users are faced with purchasing a device when the reimbursement period ends. When a device, such as oxygen therapy equipment, is used under reimbursement, the distributor or supplier usually sets it up, services and maintains it, and delivers any necessary supplies. However, at the end of the reimbursement period, patients must purchase the device if they want to continue using it, but if they do, they lose the supports that the distributor or supplier used to provide. The home user typically has not been trained to service or maintain the device and may not know what supplies they will need or where to procure them, which can lead to serious problems.

Training should be provided in multiple formats, including visual and auditory information, because individuals have different capabilities, learning styles, and preferences. Some people understand information better when it is delivered in visual format, and others understand the spoken word better. Some device users have limited education or are illiterate. Some people do not understand English well or at all. Hands-on training is generally most effective.

Patricia A. Patterson, president of Agilis Consulting Group, is an expert

in performance-based training and labeling systems for medical devices. She warns (Patterson, 2004, p. 145):

Getting information into people’s long-term memory so that they can recall it when needed—accurately and consistently—is like walking on thin ice: it’s risky, and when we’re talking medical, it’s dangerous. And it has less to do with the media (a.k.a. video) and more to do with the instructional design…. If the user needs information to perform a task—where is that information going to be stored: in their head (long-term memory) or someplace else? We try to opt for someplace else whenever appropriate for obvious reasons…. What labeling can do is to minimize the need for memory by making it accessible to the user when and where needed—like stuck to the device, in the [user interface] itself, etc.

In addition to clear device labeling and effective training, home caregivers need to have access to ongoing support, always by telephone but also through e-mail, on the Internet, or via telehealth connection. Ideally, some form of help should be available 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.

Environmental Issues

Residential environments vary considerably and can present a range of complexities for introduction of medical devices (see Chapter 10). Medical devices may be used under variable conditions involving such environmental attributes as space, lighting, noise levels, and activity:

-

Rooms may be physically crowded or cluttered, making it difficult for the person providing or receiving care to maneuver in the space.

-

Carpeting or stairs may hinder device portability or maneuverability.

-

The lighting level may be low, making it hard to see device displays and controls.

-

The noise levels may be high, making it difficult to hear device prompts and alarms.

-

The temperature may be very high (e.g., in Florida) or very low (e.g., in Alaska), which can cause equipment to overheat or stall out.

-

The humidity may be very high (e.g., in Louisiana), which can cause condensation, or very low (e.g., in Arizona), which can produce static electricity.

-

The home may not be clean.

-

The household may be busy with other residents and activities, providing distractions that may confuse people while they use medical devices.

-

Children, unauthorized users, pets, or vermin in the home can cause damage to themselves (e.g., playing with syringes), cause damage to devices (e.g., chewing on tubing), or change device settings, which may not be noticed before the unit is used again.

-

Electromagnetic interference from other equipment in the home (e.g., computer gear, such as Gameboys and Wii sets) can affect medical device functions.

These environmental influences can have a significant impact on how safe or risky a device is in the home. An example of electromagnetic interference in the home involved a motorized wheelchair. One day when the patient was at home in the wheelchair, it began spontaneously spinning around, out of control. The patient tipped backward in the chair and fell out, sustaining an injury. After the incident the patient reported that someone had been using a cell phone nearby, which may have contributed to the event (Weick-Brady and Lazerow, 2006, p. 203).

Not all medical devices stay at home. People who work may take their device along with them to the workplace. This situation has implications for device portability (size and weight) and appearance, particularly with regard to discretion. People may also take their device with them when they go out in their communities or when they travel away from home. In this case, battery life, durability, and ruggedness also matter.

A home dialysis patient who liked to travel offers an example of traveling with a significant medical device. After receiving dialysis in medical centers in 19 countries on 5 continents for 11 years, he began home dialysis and now takes a dialysis machine with him when he travels. He dialyzes himself five nights a week, unassisted, using a relatively compact, “portable” machine that weighs 99 pounds (Taylor, 2008).

The utilities available must be taken into consideration when selecting a medical device for nonclinical use. For example, for treatments that involve water (such as home dialysis), it will be important to have a clean and reliable source of tap water. For devices powered by electricity, the room will need a sufficient electrical supply (including outlets and circuit capacity). For foreign travel, this may require outlet or power adapters. The device or room will also need a source of backup power, such as a battery or generator, in case of power failure or other emergency (e.g., after a hurricane or earthquake). Some care recipients cannot survive long without the medical devices on which they depend.

APPLICATION OF HUMAN FACTORS TO HOME HEALTH CARE DEVICES

The history of medical devices used in the home is filled with stories, some successful and some cautionary. Among the successful stories, blood glucose meters with voice output are useful for a variety of users. Voice output is useful on many home health care devices because it

-

reinforces visual messages, providing redundant cuing that improves comprehension;

-

reduces misinterpretation of visual messages (including words and icons);

-

is especially helpful for infrequent users who benefit from prompting and feedback as they use a device;

-

improves user confidence and trust in the device; and

-

reduces the burden on customer service to handle repeated contact from confused users.

In addition, speech output is vitally important for people with vision impairments who cannot perceive all the visual information provided by the device.

Among cautionary tales is the story of a patient who was receiving oxygen therapy in his home. When a pressure hose came loose from the respirator, an alarm sounded, but the alarm was not loud enough to be heard over the sounds produced by the device itself (and there was no remote monitoring system in place). The patient died (Lewis, 2001).

In a study of telemonitoring and 19 elder home health care recipients, a few participants were unable to measure their own weight using a scale, most often because they needed help to accomplish the task and no one was available at the time; at least one-third of participants could not reliably interpret their blood pressure results as being normal or abnormal, and for a significant percentage of those, even periodic retraining didn’t help (Daryle Gardner-Bonneau, Bonneau and Associates, personal communication, 2009).

A study of everyday use of ventricular assist devices (to provide circulatory support before cardiac transplantation) showed that the usability of these devices affected the success and acceptance of the treatment. Of the 16 study participants, 38 percent accidentally disconnected important components of the system at least once; 38 percent reported that parts of the system rubbed against their skin (particularly the shoulder strap against the abdomen when using a bag belt); and 56 percent reported that the noises from the pump, ventilators, and alarms were annoying; however, the alarm signals were too quiet to wake 32 percent of them. Most

participants (63 percent) used a carrying case other than the one supplied, and many (44 percent) overstuffed the case with additional gear, mainly medical documents, cell phones, or eyeglasses (without which the older participants had difficulty reading the messages on the device) for which space was not provided (Geidl et al., 2009).

Medical devices used in the home should be designed to be safe and easy to use by their end-users, including the people receiving care and any lay caregivers on whom they may rely. This may require that devices have fewer features in order to simplify use, such as no memory function, or have additional features, such as new alarms (which may be visual as well as auditory) or extra monitoring functions to track device usage and adherence to treatment regimens.

It is important for manufacturers to design out hazards, rather than just add warning labels or rely on training to address problems. Not everyone reads labels or instructions—indeed, not everyone can read. Training depends on good instructors and methods, which may not always be available. Both methods rely on users to interpret the information correctly and remember it when it is needed, which is difficult for some people to do. Users would be better served if devices were designed to be more error-resistant (easier to understand and operate as well as more fail-safe) irrespective of labels, instructions, or training. As psychologist and cognitive scientist Donald Norman recommended, for devices that are used infrequently, it is better to have knowledge in the world (i.e., in or on the device) so that the user need only interpret the visual cues provided by the device, rather than depend on knowledge in the head (i.e., in the user’s memory) (Norman, 1980).

Medical device manufacturers should make a commitment to follow good human factors practices in the design of their products. They need to establish permanent human factors departments or identify and contract with qualified human factors consultants to perform the human factors analyses needed to ensure that medical devices will be safe and usable, reducing the likelihood of product misuse or abandonment.

HUMAN FACTORS ASSESSMENT

The Food and Drug Administration requires medical device manufacturers to demonstrate that they have addressed human factors issues during the product’s development process. The FDA requires design controls for all medical devices sold in the United States. These are explained in Title 21 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), Part 820 of which is the Quality System Regulation (QSR). Section 820.30, Design Controls, contains key human factors requirements in its subsections c, f, and g:

(c) Design input. Each manufacturer shall establish and maintain procedures to ensure that the design requirements relating to a device are appropriate and address the intended use of the device, including the needs of the user and patient….

(f) Design verification. Each manufacturer shall establish and maintain procedures for verifying the device design. Design verification shall confirm that the design output meets the design input requirements….

(g) Design validation…. Design validation shall ensure that devices conform to defined user needs and intended uses and shall include testing of production units under actual or simulated use conditions. Design validation shall include software validation and risk analysis, where appropriate.

The primary human factors guidance documents offered by the FDA are Do It by Design: An Introduction to Human Factors in Medical Devices(Sawyer, 1996) and Medical Device Use-Safety: Incorporating Human Factors Engineering into Risk Management (Kaye and Crowley, 2000). These documents include descriptions of human factors engineering methods, such as analytic and empirical approaches to identify and understand use-related hazards, methods of assessing and prioritizing hazards, strategies for mitigating and controlling hazards, and methods of verifying and validating hazard mitigation strategies. They also discuss exploratory studies and usability testing methods.

It is important that representative laypeople and caregivers be included in any user testing that is conducted in order to assess the safety of the medical device and its use by these populations. The potential user population may be very diverse, and it is vital to identify the users at highest risk. By studying their use of the device and its labeling to conduct essential tasks, the device manufacturer can ensure that any potential risks have been minimized, residual risks have been mitigated as far as possible, and the device is appropriate for home use.

Medical device manufacturers need to ensure device safety before marketing, and they also need to make a commitment to postmarket surveillance of their products to make sure that no unforeseen problems appear with long-term use. If problems are discovered, manufacturers must notify current users and address the problems by providing information and replacement parts or recalling the product, as appropriate to the severity of the issues.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS FOR THE FIELD

Critical gaps exist in the understanding of human factors issues for medical devices in the domain of noninstitutional health management and care. These include user issues, device issues, and environmental issues.

Maximizing adherence to treatment regimens is an ongoing challenge for home health care. Having a device at home may actually make people less diligent in maintaining their own health. “These risky behaviors can involve lifestyle changes, such as changes in diet or physical activity, or less attention to monitoring their health condition due to over-reliance on the device,” says Ron Kaye, human factors and device use-safety team leader at the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health (Lewis, 2001). Other problems with home device use, especially once the user has gotten accustomed to a device, include skipping steps rather than following proper procedures, not performing important maintenance tasks, and not communicating with health care professionals as often as they should (Lewis, 2001).

The field needs to develop methods of improving people’s ability and willingness to follow their doctors’ recommendations and to adhere to treatment regimens while visiting health care facilities less frequently. Medical personnel need to have good assessment tools and mechanisms to determine whether a particular individual is a good candidate to use a specific medical device. The attributes of the device, the characteristics of the user, and the expected use environments all need to be considered and should be integrated into the assessment program.

Some medical patients have comorbidities, that is, more than one disease or condition, for which they may be receiving ongoing medical treatment. The conditions and their treatments may be independent, or they may reinforce or aggravate one another. These effects must be understood and taken into consideration when treatment regimens are designed. However, concomitant conditions may also present the possibility of care efficiencies. For example, treatments (e.g., drug infusions) could be delivered simultaneously, reducing the time involved, or multiple diagnostic processes (e.g., blood glucose level and coagulation time) could be conducted on a single blood sample, reducing the number of samples and the amount of blood that needs to be drawn.

Device issues that need to be addressed include concern for accuracy of home health care devices, especially some of the more inexpensive types designed for home use. For example, the current international standard for blood glucose meters allows their measurements to be up to 20 percent inaccurate, but, in fact, the readings sometimes fall well outside even these generous limits (Harris, 2009). Standards for home devices need to be sufficiently stringent to safeguard the health of the user populations as well as engender trust in the technologies.

For people who use telehealth technologies (devices that communicate with medical professionals at a distance), it is important for the devices to be interoperable (i.e., work together using the same technology). For example, a home health care system can include multiple devices (e.g.,

weight scale, pulse oximeter, and blood glucose monitor) that communicate wirelessly using a common protocol (e.g., Bluetooth Medical Device Profile) to a communication device, such as a computer, a cell phone, or a dedicated standalone unit. Potentially, sets of devices designed for home use could communicate with and affect one another’s operation, such as a pain medication pump that would vary dosage based on the results of patient respiration monitoring. Having communication standards for medical devices is critical and several are being developed, but the idea of interoperability continues to be controversial among device manufacturers, who do not want to share proprietary technologies with competitors. Without these standards, however, users will be limited in the selection of devices they can purchase (that will communicate with each other) and the costs are likely to be higher.

Another concern regarding home use of medical devices is the training burden on health care professionals, particularly nurses. When a device is not well designed, it falls to the medical personnel involved to train—and often retrain—users to use it, which puts a strain on the medical system that it can ill bear. Devices that are well designed can encourage use, result in better health, and reduce burdens on the medical system, including training.

The field also needs better mechanisms for home health care users to provide feedback to medical device manufacturers regarding the difficulties and hazards associated with use of devices in the home. Professional and lay caregivers and people receiving home care are rich sources of information about medical device use safety and errors, which need to be tapped. The experiences of real users in the real world need to be captured, studied, and used to inform and improve the design of the next generation of devices used in home health care.

Environmental issues that need to be addressed include surveying and documenting the range of nonclinical medical device use-environment types, situations, and conditions. The wide variation in environmental conditions is neither recognized nor taken into consideration by the designers and engineers who develop medical devices that will be used in those locations.

CONCLUSIONS

Inevitably, as medical costs continue to climb and particularly as more devices are designed with lay users in mind, more people will use medical devices for health care in their own homes and other private and public environments.

The explosion of information on the Internet has provided people with access to more data than ever before. Individuals with health concerns have resources at their fingertips that provide information about symptoms, con-

ditions, and treatment options, which make them more informed consumers of health care services. This knowledge, in turn, enables people to be more demanding of their health care providers.

At the same time, people tend to be reluctant to blame medical devices when they have trouble using them. The professional culture in health care seems to make practitioners believe that they should be able to provide the needed care, regardless of the technology. Laypeople using medical devices tend to blame themselves if they have difficulty using a device properly, even though such difficulty often occurs because there is something wrong with the device (and not the operator). Users need to stop blaming themselves and be more demanding of medical devices. When devices are not operating correctly or are difficult or dangerous to use, users need to report those problems—to their health care providers, to their state, and to the FDA. To encourage this kind of reporting, better reporting mechanisms are needed, ones that are visible, accessible, and easy to use.

The medical industry needs to improve the health of the general public in the United States, and it also needs to reduce the cost of providing health care. Home health care promises to advance both of these goals. However, to enable good health care at home, medical devices need to be designed to be safer, more accessible and usable, and available to more people. Human factors engineering offers principles and processes that support industry to produce such devices.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Molly Follette Story was president of Human Spectrum Design at the time of the workshop; she is now a senior program officer at the National Research Council. Her expertise is in universal design of products and in accessibility and usability of medical instrumentation.

REFERENCES

Alliance for Home Health Quality and Innovation. (2008, May). The future of home health care: Containing costs while serving patients’ preferences.Available: http://ahhqi.org/download/File/The_Future_of_Home_Health_Care.pdf[accessed June 2010].

American National Standards Institute and Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation. (2010). Human factors engineering: Design of medical devices (ANSI/AAMI HE75:2010). Arlington, VA: Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation.

B. Braun Medical, Inc. (2000). Press release: B. Braun focuses on consumer education regarding infusion pump decimal and calculation errors.Available: http://www.bbraunusa.com/index.cfm?84414D8ED0B759A1E3E55CD9354BA0C5 [accessed July 2009].

Beattie, S. (2005). Technology today: Smart IV pumps. RNWeb, December. Available: http://www.modernmedicine.com/modernmedicine/CE+Library/Technology-today-Smart-IV-pumps/ArticleStandard/Article/detail/254828?contextCategoryId=5763 [accessed June 2010].

Bogner, M.S. (Ed.). (2004). Misadventures in health care. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Connell, B.R., Jones, M., Mace, R., Mueller, J., Mullick, A., Ostroff, E., Sanford, J., Steinfeld, E., Story, M., and Vanderheiden, G. (1997). The principles of universal design, version 2.0. Raleigh: Center for Universal Design, North Carolina State University.

DiConsiglio, J. (2005). Getting smart about safe infusion pump options. Materials Management in Health Care, 14(10), 26-30.

Fisk, A.D., Rogers, W.A., Charness, N., Czaja, S.J. and Sharit, H. (2004). Designing for older adults. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Geidl, L., Zrunek, P., Deckert, Z., Zimpfer, D., Sandner, S., Wieselthaler, G., and Schima, H. (2009). Usability and safety of ventricular assist devices: Human factors and design apects. Artificial Organs, 33(9), 691-695.

Hancock, P.A., Pepe, A.A., and Murphy, L.L. (2005). Hedonomics: The power of positive and pleasurable ergonomics. Ergonomics in Design, 13(1), 8-14.

Harris, G. (2009, July 18). Standards might rise on monitors for diabetics. New York Times, p. A14.

Jordan, M. (2008). Bringing medical devices home. Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry Magazine, 30(2), 62-67.

Kaufman, D., and Weick-Brady, M. (2009). HomeNet: Ensuring patient safety with medical device use in the home. Home Healthcare Nurse, 27(5), 300-307.

Kaye, R., and Crowley, J. (2000). Medical device use-safety: Incorporating human factors engineering into risk management. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Lewis, C. (2001). Emerging trends in medical device technology: Home is where the heart monitor is. FDA Consumer, 35(3), 10-15.

National Association for Home Care and Hospice. (2008). Basic statistics about home care, updated 2008. Available: http://www.nahc.org/facts/08HC_Stats.pdf [accessed June 2010].

Nemours Foundation/Kids Health. (2007). Managing home health care.Available: http://kidshealth.org/parent/system/ill/machine.html[accessed July 2009].

Norman, D.A. (1980). The psychology of everyday things. New York: Basic Books.

Patterson, P. (2004). Home alone: Designing information for device users. Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry Magazine, January, 142-147. Available: http://www.mddionline.com/article/home-alone-designing-information-device-users [accessed June 2010].

Sawyer, D. (1996). Do it by design: An introduction to human factors in medical devices. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Devices and Radiological Health. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Slater, S. (2009). Telephonic stethoscopes are used in home telehealth programs. Cleveland Home Healthcare Technology Examiner, July 16.

Story, M.F. (2007). Applying the principles of universal design to medical devices. In J.M. Winters and M.F. Story (Eds.), Medical instrumentation: Accessibility and usability considerations (pp. 101-112). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Story, M.F., Mueller, J.L., and Mace, R.L. (1998). The universal design file: Designing for people of all ages and abilities. Raleigh: Center for Universal Design, North Carolina State University.

Stuart, M. (2009). There’s no place like the home health care market. Start-Up, February.

Swain, E. (2008). Q&A: Preaching the value of human factors. Medical Device & Diagnostic Industry Magazine, October, 48-53.

Taft, C. (2007). Home use of devices creates new challenges for FDA, manufacturers. Medical Devices Today, September. Available: http://www.medicaldevicestoday.com/2007/09/home-use-of-dev.html#more [accessed June 2010].

Taylor, C. (2008). Home care devices: A new challenge for the profession. Biomedical Instrumentation and Technology, September/October, 351-356.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2009a). About MedSun. Available: http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/Safety/MedSunMedicalProductSafetyNetwork/ucm112683.htm[accessed July 2009].

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2009b). CDRH Home Health Care Committee (HHCC). Available: http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/HomeHealthandConsumer/ucm070198.htm[accessed July 2009].

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2009c). MAUDE adverse event report: Smith Medical Md. Inc. Deltec Cosmo insulin pump insulin infusion pump.Available: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfMAUDE/Detail.CFM?MDRFOI__ID=1280725 [accessed August 2009].

Weick-Brady, M. (2009). Medical devices in the home: New devices, new risks. Presentation at the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation’s 2009 Conference and Expo, June 7, Baltimore, MD.

Weick-Brady, M., and Lazerow, R.N. (2006). Medical devices: Promoting a safe migration into the home. Home Healthcare Nurse, 24(5), 299-304.